Is Clothing the Original Human Technology?

An essay on the origins of covering up our pink bits.

Over Easter, we went to a festival where clothing was optional. It was odd at first, particularly for the kids, but we soon got used to it. Even appreciated the freedom. A temporary reprieve from society’s rules. And it got me thinking—why do we wear clothes anyway?

I know the official reasons. To protect us from the elements. To make up for our lack of body hair. The snake told us to in the garden of Eden (or something like that). But those explanations don’t seem to hold up to gentle scrutiny. Or at the very least, they lead to a bunch more questions. Why do we need protection from the elements? Why don’t we have fur? How long has this been going on? So I thought I’d dig in and get to the bottom (no pun intended) of it. Or at least a few inches down the rabbit hole.

Here we go.

Why Did We Stop Being Hairy?

It’s well established that humans are pretty feeble in a lot of ways. Poor runners, poor swimmers, poor climbers, and poor at basically everything besides breathing for the first several years of life. But there’s more. Turns out we’re down the bottom of the animal kingdom for thermal tolerance too. Compared to our furry or feathered friends, humans (and many other primates by the way) can only cope with temperatures within a small range. It only has to get down to around 13℃ before we start to shiver (when unclothed). And if there’s a little wind, forget about it. Our fingers and toes start to fall off if short-term exposed to around -10℃, and somewhere above 0℃ if exposed for longer periods. Compare that to rabbits and pigeons who can remain relatively comfy down to around -40℃.

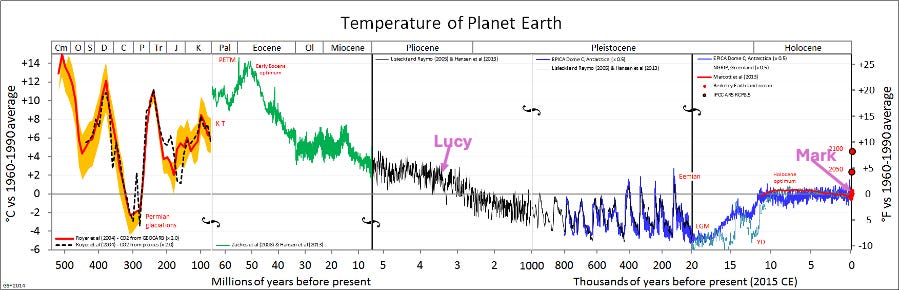

Why would shedding our warm fur have conferred any evolutionary advantage whatsoever? Especially since we evolved during an extended period of regular cold snaps, when large segments of the Earth—that we were interested in moving to—were covered in glaciers.

OK, some would argue that we haven’t altogether stopped being hairy:

But even Mr Ruffalo is a far cry from how we imagine Lucy the Australopithecus and her friends who roamed the Rift Valley 3.2 million years ago:

So some time in between Lucy and Mark, something happened that made it advantageous for early humans to become bare skinned. What?

One theory is that it happened quite early in our evolution. Maybe between three and four million years ago, when things were much warmer. (Maybe Lucy wasn’t so hairy after all.)

This is supported by evidence from the DNA of lice. There are three types of lice that pester humans: head lice, body lice, and pubic lice. The emergence of these lines from common ancestors gives us clues about when those environments may have begun their independent existence. Indeed, the appearance of pubic lice, corresponding presumably to the separation of pubic hair from head hair, has been mapped to around 3 million years ago. This corresponds neatly with when people supposedly emerged from the cool forests to the savannahs and began long-distance hunting in that hot environment (and sweating, by the way). That transition is debated too, but it’s not what we’re talking about today, so let’s just go with it as an explanation for bipedalism for now.

This is known as the Thermal Model of human evolution and it is described in great detail here (the paper where a lot of the stuff I’m telling you comes from). But there are some other theories that could interplay with that model or more fully explain our lack of fur:

Relief from parasites. Giving lice and other pests less area to inhabit may have given an advantage by lowering disease transmission.

Living by the water. Body hair doesn’t give as much thermal protection when wet. However, the aquatic ape theory doesn’t seem to hold water, for reasons explained very well here.

Smooth, disease-free skin might have been a turn-on to our forebears, leading to the selection of hair-free partners and less hairy offspring.

So When Did We Cover Up Again?

I guess we could have done like the chimps and orangutans and just stayed in the tropics where the temperature suited us best, and many people did. Those that would end up inhabiting Australia probably traveled all the way there without leaving the tropics, and indeed, they continued living mostly naked for their 50,000-odd years of alone time on the warm continent. Even those living in cooler, southern areas developed greater tolerance for low temperatures, and evidence of clothing use is only found in Tasmania during the coldest periods of their inhabitation.

But elsewhere, it just got too cold. And people figured out that if they took the skin of that animal they’d just slaughtered to eat and treated it with a stone, they could sling it over their backs and stay almost as warm as the deer it’d come from. There are plenty of clues telling us when and how this all came about.

Here’s a neat video summary:

The best evidence comes from three places:

Clue Number 1: Needles

Ancient sewing needles have been found in France, Egypt, Greece, India, China, and Japan among other places, showing their early use in a variety of climates. They date back 50,000 years or more, and were even used by hominids other than homo, indicating that clothing (or at least joining bits of cloth together with thread) wasn’t exclusive to our species.

Clue Number 2: Tools for treating animal hides

Sewing with an awl or needle is nevertheless more advanced than just treating animal skin to use as body covering. Recent discoveries in a cave in Morocco indicate humans were working leather up to 120,000 years ago. Tools for scraping hides (with possible other uses like shelter) goes back even further, possibly as far as 780,000 years ago.

Clue Number 3: Body lice

The species of lice that likes to live in our clothes split off from head lice around 170,000 years ago, which coincides with the start of an ice age, so that could be when we first got dressed and went out (of Africa).

Indeed, this timeline broadly puts the development of clothing alongside a number of attempted human expansions beyond our home continent, which are estimated to have happened over multiple waves ranging from around 200,000 to 40,000 years ago.

Clothing as Innovation

So, now we have these upright apes who accidentally got rid of their most effective warming mechanism, leaving them dangerously exposed to the elements just as half the world is freezing over on a regular basis. At the same time, they’ve started to reap some benefits of being a little bit clever. Their exposure to the cold would have encouraged them to master fire and start to cook, massively expanding their dietary options and the nutritional value they could gain. They had to develop ways to protect themselves, both by creating shelters and by clothing their bodies. What’s more, they started to get creative and decorate their bodies with dyes, beads and shells (details here, pg 56). Their bare skin became a canvas for art, which increased creative thinking. Who knows whether they decorated themselves before their cave walls, but whatever the order, the outcome was an ability to convey more information to one another by visual communication.

So these adaptations not only allowed them to master new arts and come up with new inventions, but it gave them the unprecedented opportunity to start roaming further afield. By 120,000 years ago, they were living all across Africa in a number of different habitats. While some of the efforts to move to other continents didn’t succeed, the most recent dispersal of between 70,000 and 50,000 years ago is thought to have resulted in modern humans spreading throughout the world in a lasting way.

Presumably, the convenience of wearing the furry skin of other animals outweighed any benefit of growing back our own hairy hides.

And then along came…

Modesty

At some point, people somewhere decided that bits of us were too rude to be seen in the light of day (the influence of a no-legged creature is still a topic for debate). From what I could find, this is a fairly recent development, perhaps well into the modern era, and is heavily influenced by culture.

Nowadays, modesty norms vary, but it’s pretty common that genitals should be covered at a minimum, no matter how hot the environment people live in:

Or how elaborate the show…

This could be for protecting our precious life-reproducing parts from the elements. But no other animals are worried about that, and we have kept a handy covering of fur there, despite the lengths many of us go to to remove it. Hot wax between your butt-cheeks, anyone?

Is it maybe because the sight of another’s intimate bits will send humans into a sexual spin? I’m not sure. I didn’t see a single erect penis the whole time we were at the festival, and everyone was respectful and cool. It was all very wholesome from my perspective, but then, I was there with my kids.

Admittedly, there were instructions regarding consent on the toilet walls, several workshops on the same topic, and one evening, we heard a voice drift out from a nearby tent saying, “I’m taking my jacket. There’s a very low chance I’m going to be in an orgy tonight, so I don’t need to look good.”

So maybe there’s something to it. There’s only one other animal I know of that enjoys sex as much as we do. Our closest cousins, the bonobo (aka pygmy chimp), who use sex freely for reasons ranging from bond formation, to conflict resolution, to simple greeting. They’re the only other animal that regularly has face-to-face intercourse and engages in kissing.

So maybe if we were naked like bonobos, we would be as deviant as they are.

When bonobos come upon a new food source or feeding ground, the increased excitement will usually lead to communal sexual activity, presumably decreasing tension and encouraging peaceful feeding. -from Wikipedia

Shocking, I know. But I digress.

OK, one more.

…female bonobos engage in mutual genital-rubbing behavior, possibly to bond socially with each other, thus forming a female nucleus of bonobo society. The bonding among females enables them to dominate most of the males.

Make of that what you will, girls.

Anyway, back to humans.

I couldn’t find exactly when or why it became rude to look upon our fellow humans’ genitals, bottoms, and breasts.

If you know more, please fill me in, because I’m super curious, and the history of modesty could certainly fill its own article down the track.

So that’s nudity

The undisputed norm across the animal kingdom, every other Earth kingdom, and even what we imagine from outer space.

Whether for practical or prudish reasons, shedding our fur and replacing it with clothes was potentially an important development in human evolution that may have directly or indirectly contributed to our learning to use tools, getting more creative, communicating with each other in new ways, and increasing our dexterity. It almost certainly gave us the portable adaptability to move to more corners of the world than any other above-ground, land-dwelling species. And I didn’t even go into economic aspects of it. What were the implications of developing things of value that were not edible and were infinitely interesting and modifiable? Maybe a story for another day. Let me know if you’re curious too or can add to or correct some of what’s here.

As for our brief foray into a prehistoric-like world of open nudity, when we got home, two excited kiddos recounted every highlight to our two fish-sitting house guests—the river, the rope swing, the Fun Shop where they bought their light-up pois and baton, the mud bath, the body painting… Do you think they mentioned the nudity?

Not once.