The Hyperion Competition: How to get to another star

The visionaries imagining our future among the stars

It’s the year 2130. Earth is home to 15 billion humans who live in high tech luxury, while leaving a minimal footprint on the planet which is covered with a rich wild population that enjoys a carefully regulated climate.

In the observation deck of the lunar outpost, Artemis Station, the entire crew gathers together in anticipation of a very special arrival. Robots and biologics alike count down the moments until a signal from one of the miniature drone swarms that has been sent to Proxima Centauri arrives from their mission exploring the nearby star system’s planets and moons.

The red light that has been flashing on the screen suddenly starts racing to the right, followed by rapid-fire text.

“What does it say?” gasps a breathless voice from a back row.

“Wait, let me read. It says…” The Mission Lead sits up straight in her chair. “Proxima b has a breathable atmosphere!”

A cheer erupts and quickly dissipates as the crew quiets to hear the next words to come out of her mouth. “And it has liquid water!”

Another cheer, and finally, the Mission Lead taps a few keys and then turns to look at her colleagues. “The images have arrived!”

The crew look on in awe, impatient for the pictures to be beamed down to Earth to share the incredible news that a habitable planet has been confirmed.

Project Hyperion is a go.

This is the kind of scenario that could see humanity taking to the stars and leaving our solar system to explore our local galactic neighborhood.

But how?

The Hyperion Competition

The Initiative for Interstellar Studies (i4is) recently ran a competition that asked teams of architectural designers, engineers, and social scientists to design spaceships that could take humans on a 250-year journey to reach our closest neighboring star.

The rules dictated that the ships had to house generations of living humans, rather than relying on cryogenic freezing or comas. The vessels should have the capacity for 1000 ± 500 people and have artificial gravity. Proposals needed to address living conditions, life support, and knowledge transfer. The full guidelines are here.

In July 2025, the winners were announced. Before I show you them, have a think about how you would design a ship that’s essentially a closed ecosystem equipped for long distance travel where the people who embarked on the journey would never live to see the destination, and those that do arrive have never known life outside.

There were 13 entries that either placed or received honorable mentions. I went through them all and compared the technical, social, and cultural elements, before running through a bunch of aspects of the designs to see where they diverged and what they agreed on1.

1. The ships

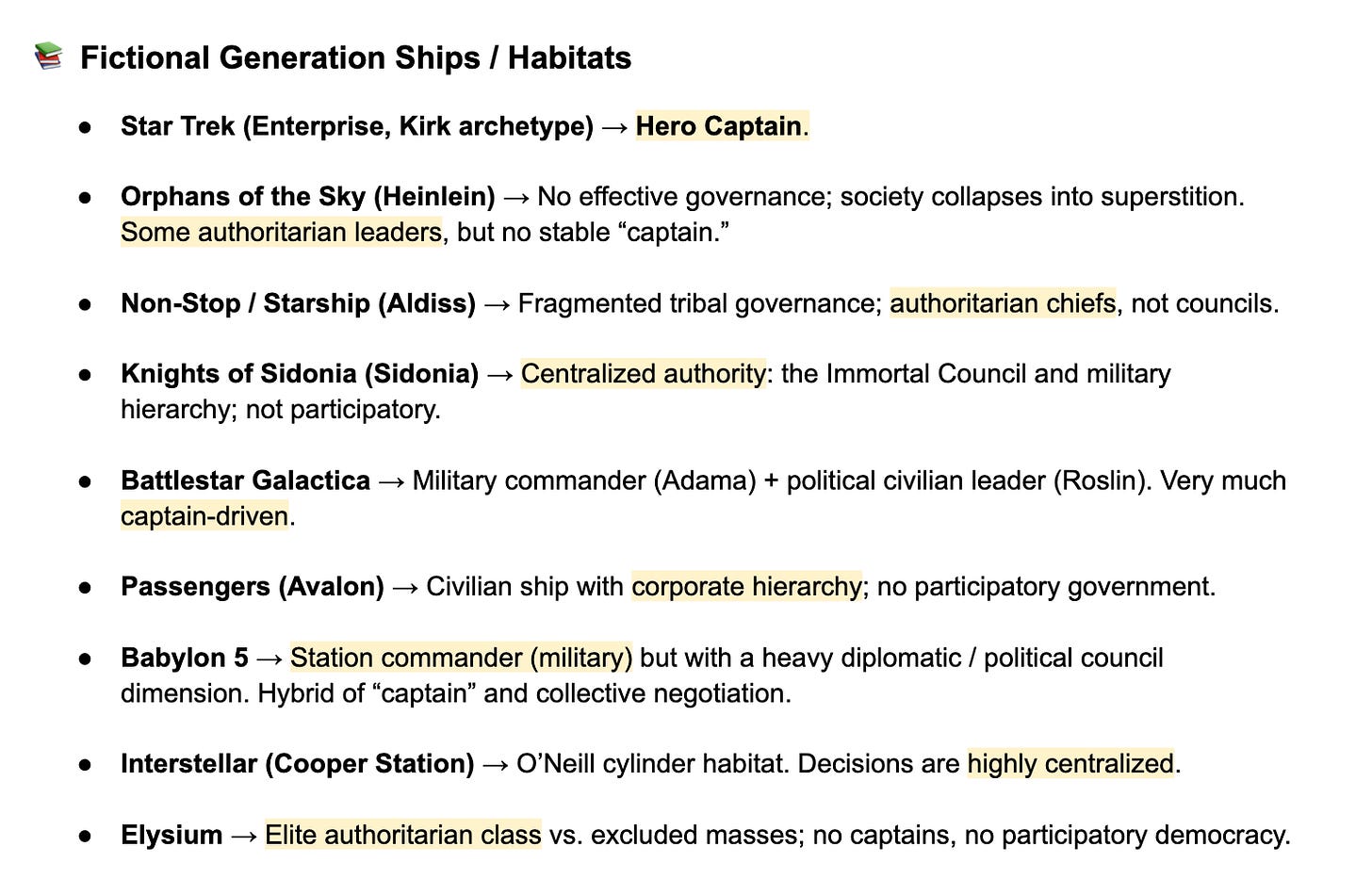

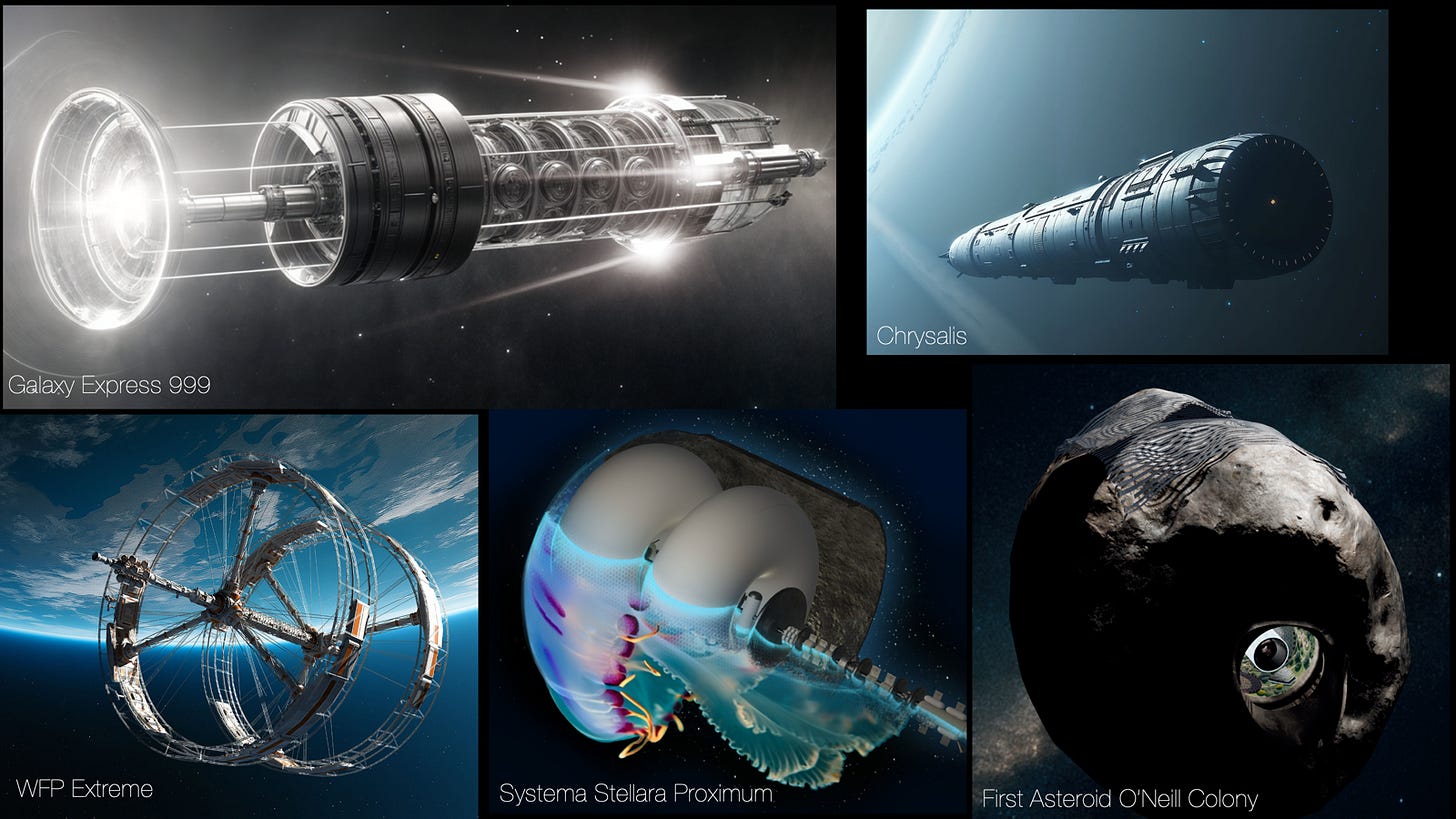

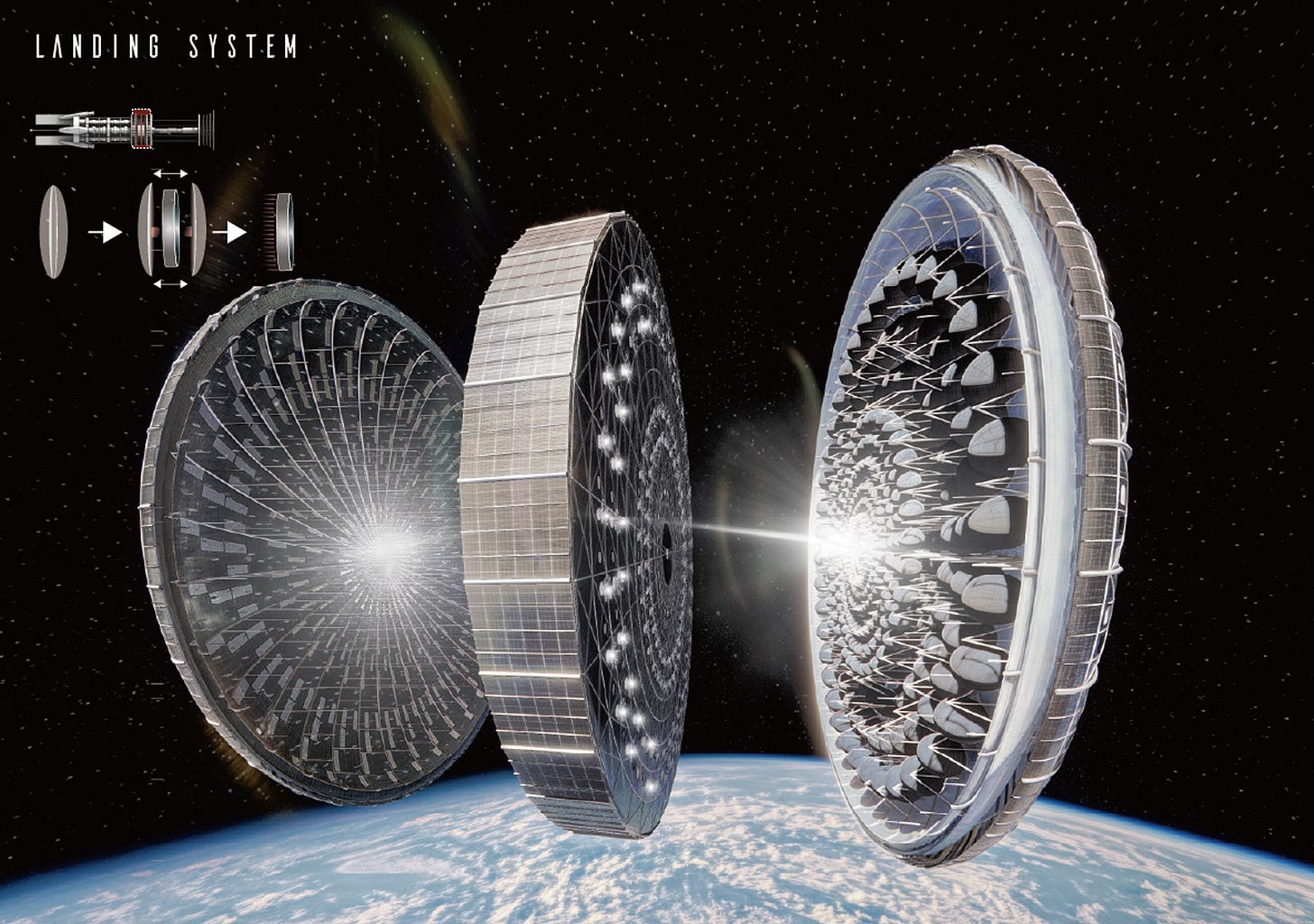

Here are the ship designs (excluding Arkkana and Undagila as they didn’t have decent exterior shots in their entry packs—see them all here):

Spinning things with central, 0-gravity corridors and 1g at the outer walls. The propulsion, energy, and technology is interesting, and the air, water, and food considerations even more so.

But what struck me the most was the information that emerged from the social sciences. What governance structures they imagined, the family set-ups, the ways the people would spend their time and pass on knowledge from one generation to the next.

2. Social structures

a) Governance

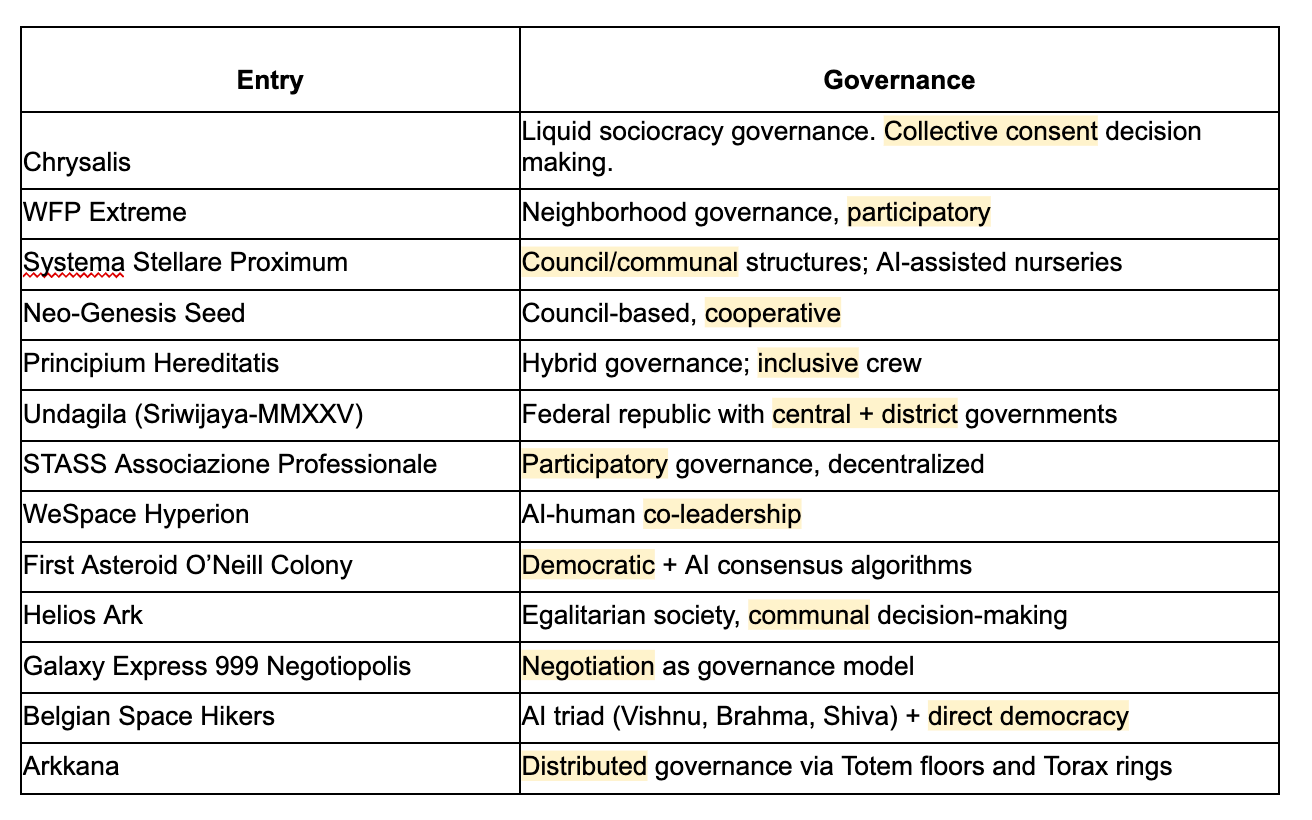

What would you do? Would you install a “Captain Kirk” who could fearlessly lead the crew to new horizons or would you attempt to use some kind of socialist, participatory model?

Well…

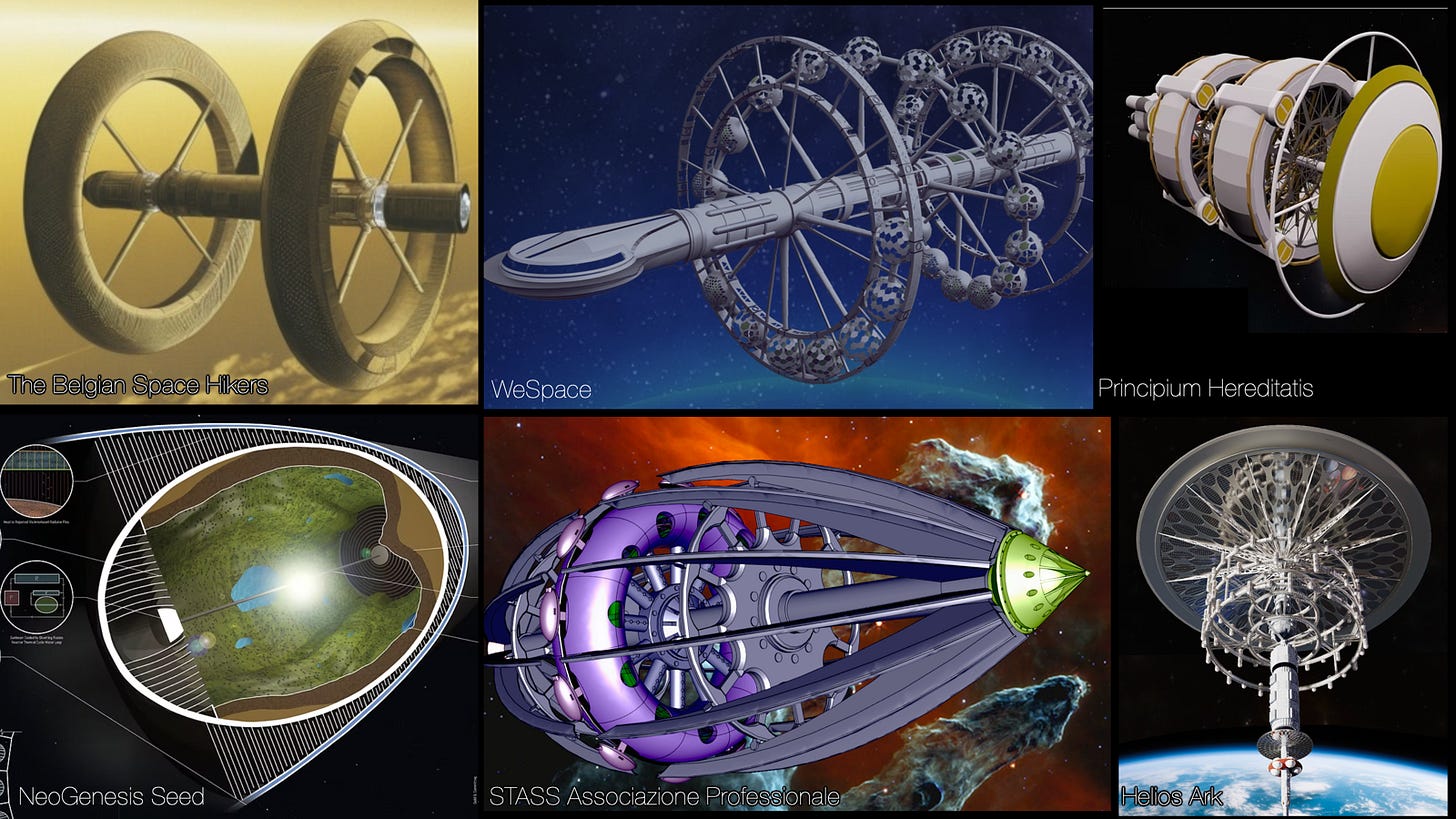

Many of them included AI in their governance models, but how many had a central authority figure? Zero.

I think the reason for this was that the designers imagine that this is the best way to go the distance. An autocrat seems like a recipe for power struggles and discord.

Now compare that to how sci-fi authors imagine their governance structures:

It seems that scientists who seek to design an ideal future civilisation envisage a cooperative structure, while authors who seek to entertain readers use power dynamics as fuel for drama. Of course, that drama plays on our understanding of human nature, and note also that fiction is character-driven and happens in scenes, while an idealised ship design gives a more general overview of life onboard.

Still, the different attitudes can be identified in the scientists’ ideas:

…power consolidation would likely (at least for a portion of the population) lower quality of life and reduce individual liberties—Neogenesis Seed

The political system and social organisation of Chrysalis is designed to avoid possible social degeneration into oligarchies, social fragmentation, class diversity and ideological polarisation, power centralisation processes and other deviations that may arise during the passage of generations of inhabitants.—Chrysalis

A notable exception to these patterns is Aurora, by Kim Stanley Robinson, a generational ship novel that starts with a distributed government reminiscent of the entries to the Hyperion competition, but as the technical systems begin to fail, the citizens seek out decisive leaders to guide them to salvation. Could it be that the ideal of collective decision-making only holds in an artificial construct, and that we crave leaders when times get hard?

These are all questions I’m grappling with as I conceptualise and write my own generational novel, Journey to Kyron (J2K). The technical components of the ships in the competition are super handy to help me think of aspects I might not have considered, and the social structures inform my storytelling.

My ships are much bigger than the specs in the competition demand—there are ten vessels that house 100,000 citizens each, and they all have a “wild island” where other animals live without human interference. They are designed to be spacious so people don’t feel cramped, considering that they have to spend their entire lives inside them.

And my ships do have captains—two per vessel and a mission captain that is selected from among them. I’m still deciding how much power the captains should have, and whether there should also be elected leaders that are more about leading the population and less about driving the ships. There seems to be an underlying assumption that the ships kind of drive themselves. Sounds reasonable, but there are still technical considerations that need to be overseen. Which brings me to…

b) AI

We can’t really imagine being capable of getting to another planet (or any other significantly advanced technology) without the help of independently intelligent computers. They are present in all the entries but mostly embedded within the systems as assistants and engineering support. In fiction, they tend to be personified to a much greater degree (although WeSpace had a commanding AI in government, and the Belgian Space Hikers imagined an AI triad (Vishnu, Brahma, Shiva) as guiding entities—almost religious figures!

My story has a central AI called AiLa, which everyone can talk to through their personal communication device (note that I made that up before ChatGPT became a thing—just saying). AiLa is embodied through characters like the Mission Teachers, which give personalised education to the youth of the mission and support the human teachers who lead groups in learning.

c) Education

For the most part, my ideas align with the competition designs. Some combination of AI teaching, apprenticeships/mentorships, and early group teaching was common. The fictional examples I looked at mostly had more traditional, group-based teaching that was used as propaganda or population control in some instances, especially the more dystopian, cautionary stories.

Is the future of education more personalised and specialised?

d) Interpersonal dynamics

In a society that depends on one another for harmony and survival, does a nuclear family model make the most sense? It was common for the designs to include more loose family structures than what we’re used to. One of them gives an initial ratio of 60%-40% females to males, for obvious reasons. My book also shows a variety of family configurations, which sometimes leads to interpersonal drama. I don’t think all cultures will give up our current norms very easily, but I may be wrong.

Given that the societies have to live in closed systems, the entries all had to address the question of population control. Some included voluntary euthanasia, and all of them required citizens to obtain permission to have babies, whether these would be born by traditional means or using exowombs. These elements also feature in J2K, although I spend a lot of time discussing the more intimate details, like how they prevent pregnancies (I’m currently leaning towards vasectomies for males early on, which are reversed when they get the go-ahead to breed), and how they deal with periods. None of the entries or the fictional examples go into details on those things, it’s more just stated as fact that people need to adhere to the rules.

e) Work

In J2K, I try to avoid language constructions like “I’m a…” when talking about characters’ jobs, which is actually incredibly hard. I’ve started to try to incorporate this into my general vocabulary, avoiding identifying myself or others by our occupations, and rather saying things like “I work as a…” or “I’m in…” Nevertheless, the characters contribute and seek meaning through their daily pursuits, which include teaching, farming, and leadership, as well as entertainment and art.

Many of the Hyperion entries valued variety and change in occupation, allowing the population to pursue multiple occupations. They addressed work either in terms of the technical requirements of looking after the ships and their occupants or they focused on pursuing satisfying hobbies and artistic pursuits. Asteroid O’Neill Colony for example, used a “WORBY” model, combining work and hobbies to allow crew members to have meaningful, enjoyable contributions to society. There was also an emphasis on teaching and knowledge transfer that was common across entries.

Money was mentioned in a few, but generally as a problematic source of potential conflict. Given the closed environment, they either used a points/merit based system or simply assumed that all would be provided for and resources distributed equitably.

Starships as Mirrors: What These Designs Reveal About Our Future

There are so many more things I could talk about—food, heirlooms, culture, police, surveillance… But I wanted to finish up by thinking about how the imagined future of humans as a space-faring species informs our actual future. Sometimes, when I talk to people about how I’m writing a novel about humans going to another planet, they ask why. What’s the reason for the journey? Beta readers have also questioned this. Sometimes, people assume it must be because the Earth has been destroyed and we are forced to expand or perish.

I prefer to think of it as a natural step in our evolution though. We would go to another planet if we could. Just like we went to the moon and we are thinking of going to Mars and beyond. It’s in our nature to explore, discover, and journey beyond our home planet.

What that looks like is anyone’s guess, but the Hyperion Competition, and the i4is more generally, are making these ideas accessible and that’s so inspiring. If I can do my part by imagining a journey from an optimistic perspective, maybe I can play a small part in humanity’s dream to go further, to know more, and do more than we ever thought possible. That hope drives me forward.

Let’s keep dreaming and building!

I enlisted some help from ChatGPT for this task.

I thought this was a great project and was also very impressed at the winning team's effort to develop social and economic models: https://substack.com/@reiditwrite/note/c-143692006?r=wtpo

Pity I didn't know about this competition, as I would've most likely entered it. The problem though would've been their stipulation of population size (500-1500), and clearly also the journey time (i.e. generations) - this implies a very slow ship indeed if it's only going to the next system. I see a basic flaw there, which is that if it takes like 100 years to get there then there's no point, because within that hundred years the science of propulsion would've advanced sufficiently to cut that journey time down by an order of magnitude at least. Equally, by the time humanity has the technology to build any of those designs then it would also have that propulsion technology and the logistics/resources to build it.

Still, leaving those considerations aside, and notwithstanding I haven't (yet) read any of the proposals in detail, I am wondering whether or how much actual psychology they employed, because that's the crucial factor. In my own 'journey to Centauri' novella (it's in my Rejected Messages book, linked on my site) it builds the entire population around the social cognition number (aka Dunbar's number), which is 150. Except they don't start with 150 they start with 32 carefully selected couples aged 18-22 or so, the idea being they have children on the way. It also helps they have a shorter journey time (no more than 15 years), and the ship is more than capable of providing for actually a lot more than 150 (e.g. if they have to stay in orbit for a while and sort out the alien pathogen issue). The oldest children would be becoming teenagers by the time they arrive.

As such, because they are well within that evolutionarily programmed optimum population size, they can have an entirely communist/communalist social order. Yes, people have jobs like 'captain', but that's based on merit, not hierarchy (i.e. best person for each role). They don't have money because they share everything. The AI is simply there to assist and monitor stuff like life support, although it also has a simulation subroutine (that requires a much longer essay) and would probably end up connecting up with the galactic AI. I'm guessing the Hyperion people are assuming Centauri is uninhabited (not very likely IMO).

The other most important consideration is the human spectrum of needs (what Maslow called a hierarchy of needs), each of which need requires an opportunity for fulfilment, otherwise humans get seriously stressed (with all the social problems that produces). The problem with the current social order, or why it's a dystopia, is because one or more of these needs is prevented for everyone. Any hierarchical system would probably work in the same way and degenerate into a dystopia, which is also why they need to take the social cognition number into consideration.

It is interesting, though, that it seems all the entries imagined some version of a communal/liberal socialist social system - which is far more in keeping with innate human nature, of course. And it would have to be a system like that, because otherwise humans wouldn't be allowed out of their solar system in the first place... And yeah, that really is another story...